What is the connection between nature and art? My daily walks along the Potomac prompt many of my paintings. I might juxtapose the russet red of new growth with the greens of

more established growth. But at some point, the painting diverges. I start to see the nature of the painting, which has its own demands.

I think of each painting emanating a unique light. There is the sunlight seen through a translucent blade of grass, or the menacing light of a noir movie. But the light from a painting may suggest a light we see in nature, but it always diverges, morphing into some other light. How many lights can there be?

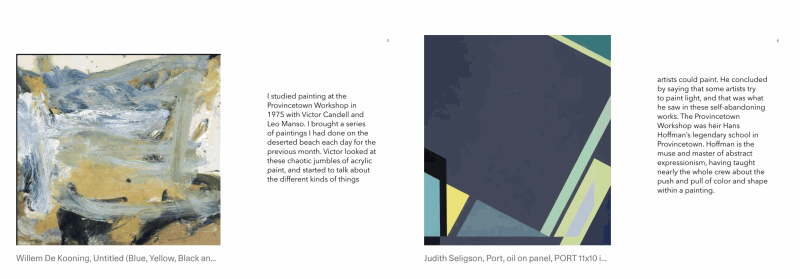

I studied painting at the Provincetown Workshop in 1975 with Victor Candell and Leo Manso. I brought a series of paintings I had done on the deserted beach each day for the previous month. Victor looked at these chaotic jumbles of acrylic paint, and started to talk about the different kinds of things artists could paint. He concluded by saying that some artists try to paint light, and that was what he saw in these self-abandoning works. The Provincetown Workshop was heir Hans Hoffman’s legendary school in Provincetown. Hoffman is the muse and master of abstract expressionism, having taught nearly the whole crew about the push andpull of color and shape within a painting.

“It would be virtually impossible to overestimate Hofmann’s importance as a teacher. Over half the original members of the American Abstract Artists were Hofmann students.

Many second generation Abstract Expressionists worked with him as well. He provided scholarships to those unable to pay full tuition, and frequently allowed students to work for him in exchange for instruction. Whether or not they attended his classes, many artists knew of Hofmann’s ideas. An essay entitled ‘Plastic Creation’ was published in the Art Students League magazine during the winter of 1932-33, and a series of six lectures given during the winter of 1938-39 was attended by Jackson Pollock, Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, Clement Greenberg, and Harold Rosenberg.In his teaching, as in his art, Hofmann advocated nature as a starting point.” (Hans Hofmann Smithsonian Museum of American Art)

Still, the question remains. What does geometry have to do with nature. There are the glorious Fibonacci series in shells and plant life. Geometry made a big impact on painting with the introduction of perspective into paintings in the thirteenth century. But what happens when an artist abjures perspective’s third dimension for the push and pull of color and form?

There are no straight lines in nature. My work in recent years has been all about straight lines. How does the eye perceive light? How does a painter, using blobs of oil-infused pigment, create irridescent light passing through a blade of grass?

Juxtaposition of colors. The impressionists broke up the painting surface into dots and dabs of paint. I’ve broken it into larger and smaller geometric shapes. Exactly how much of one color next to how much of another, in what shape, will yield the illusion of light?

These paintings can be read simultaneously as an elevation and as a plan. The aerial, or plan view is further emphasized by the use of multiple panels in my recent work.

In 2013 I made a video called Spring 2013 - A Visual Essay, in which I juxtaposed my paintings with photos I had taken in our garden and along the river.